- Fellow Highlights

Living the Questions

What matters? When you set out to design something—whether a neighborhood, an information network, or a healthcare system—what are its most important elements? How do you extract the essentials from the onrushing flow of information? Then, how do you apply what you’ve learned to the needs of real people in their communities? And, perhaps most important of all, how can people appropriate and transform these learnings to improve their lives?

For more than a decade, Prabhjot Singh, a 2005 Paul & Daisy Soros Fellow, has been asking questions like these, and it’s his mission in life to find answers to them. To do that, he travels across disciplines that typically divide entire fields of inquiry: fields such as medicine, political science, genetics, global health, international development, systems design, and information theory.

These days, Prabhjot doesn’t spend his time in the lab or at academic conferences. For one, he’s a hands-on clinician at City Health Works, an innovative fusion of lay workforce training and community-based primary care founded by his wife, Manmeet Kaur, in East Harlem.

He also leads the One Million Community Health Workers Campaign, an initiative that substantially augments existing community-based primary care systems in sub-Saharan Africa. The same man who used to grapple with big data in the lab has been engaging with local communities in 14 African countries, and closer to home with one of the most challenging neighborhoods in New York City.

When he’s not at the clinic, Prabhjot is Director of Systems Design at the Earth Institute and Assistant Professor of International Public Affairs at Columbia. He arrived on the shores of the Earth Institute in 2006 at the invitation of Jeffrey Sachs—distinguished author, academic, and economic

adviser to heads of state all over the world.

“At the start of my postdoctoral fellowship, Jeff asked me to work on community health workers at a systems level,” he says. “The One Million Community Health Workers Campaign is the practical outgrowth of that work.”

Not long ago, health workers were given tomes of information before going out into the field, he explains. Once out there, however, they tended to forget much of what they had learned. “We used to think the answers lay in more education, more information, and more training,” he says. “But when you’re in a rural setting, and you’re alone with someone who has a high fever, there’s no time to consider disease vectors and the life-cycle of the parasite. You need a rapid malaria diagnostic set, for example, or rehydration therapy kits for children with diarrhea. Community health workers operate at the interface of two worlds: They have sufficient understanding of biomedical technologies, complemented by deep understanding of local context, including when

interveners are no longer welcome.

“Community health workers used to be considered the least valuable link in the healthcare chain,” he continues. “Today, they’re at the very heart of primary care, precisely because of their ability to form deep and lasting relationships. I also see them as champions of grassroots democratic traditions, both here and abroad, by dint of their work as community advocates.

I’m thankful to Jeff for giving me the opportunity to have a global vista and to think for myself,”

he says. “I love what I’m doing.”

On April 3, 2014, Prabhjot co-hosted an event billed as an “Intimate Conversation with

Jeffrey Sachs” at the Open Society Institute in New York. Contentious, open, and even raw

at moments, the conversation was by all accounts unforgettable. This special event was

sponsored by the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellows’ Association, the Fellowships’ alumni platform

for ongoing social, professional, and creative interaction.

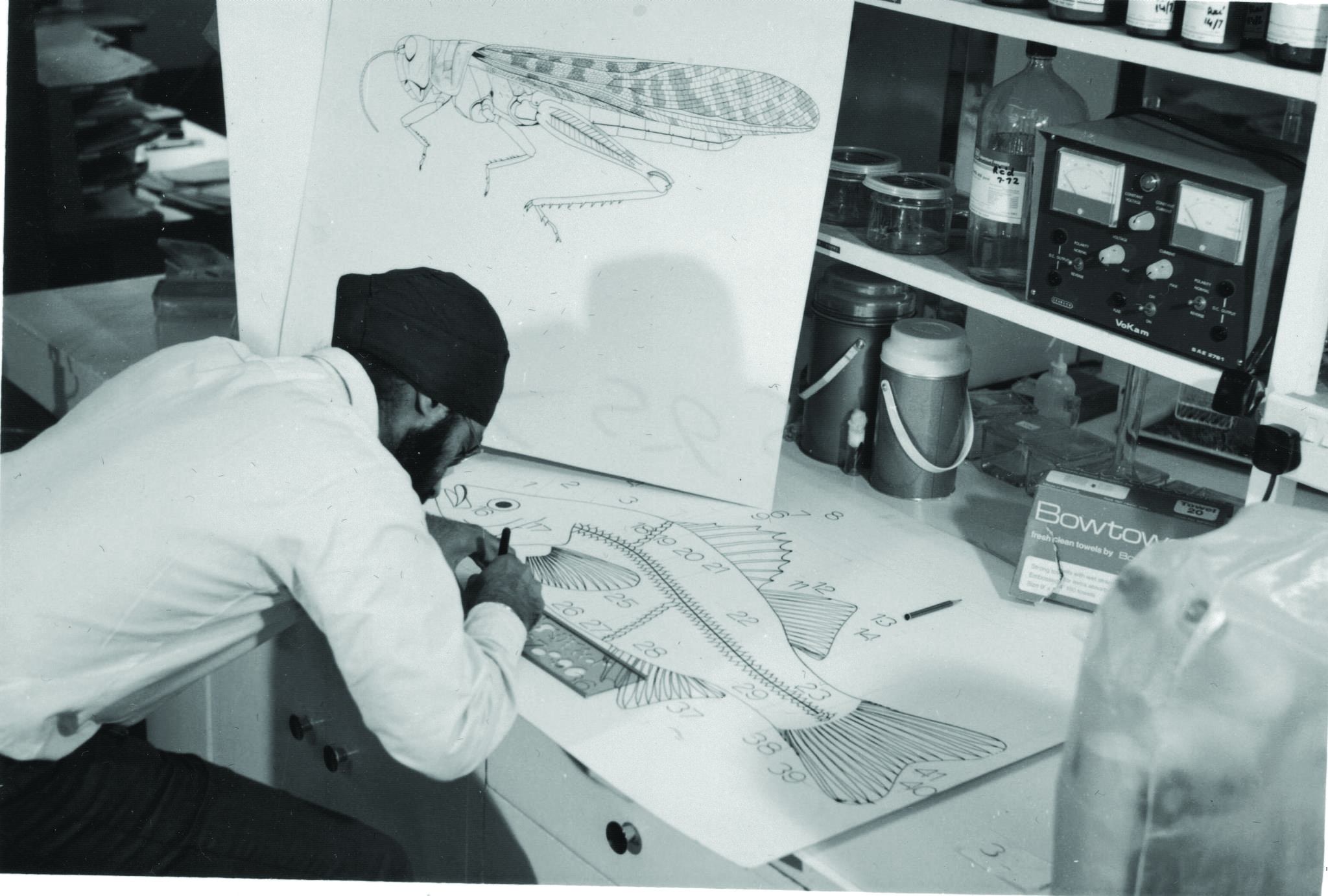

Photo Credit: Julie Brown

Tracing the Path

For his achievements, his promise, and the sheer audacity of his ideas, Prabhjot has garnered a long list of grants and awards. He’s a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Young Leader and a Truman National Security Fellow—yet winning the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship for New Americans in 2005, he says, was the most important of all.

“The Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship came at a pivotal moment in my personal development. Through my diverse academic interests, I was seeking a path to something that’s hard to identify, something I’ll call the ’substrate’ of social cohesion. In supporting two years of my MD/

PhD studies at Weill Cornell Medical College and Rockefeller University, the Paul & Daisy Soros

Fellowships played a critical role in helping me build the road I’ve been traveling in the nine years since I received that life-changing award.

It has been a bumpy ride so far,” he adds, “but a great one.” While still earning his MD, Prabhjot quickly found a way to combine his love of information theory with his need for social engagement. He developed a large-scale database to help the International Rescue Committee (IRC), a venerable

humanitarian relief organization, supply refugee camps with urgently needed resources, and to track and update these resources in real time. “I patched together a system that was implemented across many countries. Later, it was used as the basis for a more sophisticated model that’s in widespread use today.”

Soon thereafter, Prabhjot’s passion for science found a home at Rockefeller University. In 2010, he emerged with a PhD in Neural and Genetic Systems. That’s a specialty requiring the scientist to sift through vast quantities of information and pull out the most relevant data sets according to the problem at hand. How, for example, can you predict the evolution of an organism from its genetic code? Its ability to adapt to a changing environment? Its behavior?

“There are networks of influential genes in biological processes,” Prabhjot explains. “But what do we mean by ’influence’? We’re back to the question of ’what matters.’ And the only way to find that out is to ask, ’What does it matter for?’” One major upshot of Prabhjot’s research has been the counterintuitive insight that in many cases, less information is more.

“Small amounts of information are often sufficient to allow you to understand the structure of things,” he says. “The question then becomes: What is that minimum?”

Beyond the what in information theory, Prabhjot is also keenly aware of the who: who possesses, curates, and controls information. Prabhjot believes the fruits of research should be transferred to people in particular socio-cultural settings as quickly as possible. At the same time,

scientists need to be mindful of what works at the local level as they analyze and revise their own findings.

A Holistic Thinker in Fragmented Times

It’s not that Prabhjot ever had to make a huge effort to high-jump over disciplinary lines. He

never recognized them in the first place. In his junior year at the University of Rochester, Prabhjot launched the Journal of Undergraduate Research, an interdisciplinary journal of ideas. That was back in 2001—and the journal is still a going concern. Around that same time, he took a class in the history of medicine and discovered Rudolf Virchow, a 19th-century German physician, anthropologist, and political theorist remembered today as an early champion of public health and the “father of pathology.” In Virchow, Prabhjot found a kindred spirit and a mentor, if not one he could meet with over coffee. But he has often returned to contemplate his works.

“When I got to medical school, I was in for a rude awakening,” he says. “It was all very biomedical. Where was the human side of the story? Where was the historical and social context for the practice of medicine? Where was Virchow?” Prabhjot had no choice but to get with the program, hunker down, and study hard with the rest of his colleagues.

Then, in 2004, the young change-maker joined forces with four of his classmates to found the first-ever free clinic at Weill Cornell, run entirely by students. Soon, though, he began to see how hard it was to run a healthcare enterprise—even a very small one.

“Healthcare delivery is so much more than patient care,” he says. “You need to deal with how it’s financed and regulated, how healthcare professionals are credentialed, how diseases and conditions are defined and treated, and much more. Fortunately, I was able to learn from these early experiences. Today, City Health Works reflects a very different approach to healthcare. The East Harlem-based clinic is embedded in neighborhood housing and connected to a large network of primary care clinics, insurers, and community-based organizations.”

City Health Works isn’t just another health resource, he says. It’s a social enterprise, benefiting from the input of multiple partners across the for-profit and non-profit sectors. It trains peer health coaches, this country’s equivalent to community health workers in developing countries, providing jobs in East Harlem and boosting the local economy. It complements and supplements the city’s

overused hospital-based healthcare system by helping patients avoid visits to the emergency room and set personal goals that lead to better health. And it takes advantage of agile mobile technology to communicate with partners, staff, and patients.

“Right now, what we’re doing is small, but the pressure to expand is growing. If we continue to get positive feedback in our neighborhood, and if we crack the code on how to sustainably finance this work, we’ll share what we’ve learned with neighborhoods in other parts of the country.”

At Times, a Persecuted Minority

Asked whether his Sikhism has something to do with his passion for social engagement, Prabhjot explains that service (seva) and remembering the bigger picture (simran) are, indeed, hallmarks of the Sikh faith. Sikhism is a monotheistic, egalitarian religion founded in the early 16th century in the Punjab region of Pakistan and India. Its overarching ethos is to serve humanity (sarbatdhaballa). But that’s not what his attackers saw on the evening of September 21, 2013.

That very day, members of a Somalia-based Islamist group had mounted an assault-rifle attack on the Westgate Mall in Nairobi. Relieved to learn that his relatives there were okay, Prabhjot went out for a stroll along Central Park North, near his apartment building in Harlem. From behind, a voice shouted, “Osama! Terrorist!” A stream of young men on bicycles proceeded to chase and overtake him. Multiple fists rained down, fracturing his jaw and knocking his teeth loose. He spent the rest of that night in the ER at Mount Sinai, bruised and bloodied.

Prabhjot’s wounds have mostly healed since that gruesome event. His attackers remain at large.

A few days after the attack, appearing on Huff Post Live, Prabhjot expressed empathy and even forgiveness for his tormentors and offered the following comment: “Ultimately, I think to simply go out and punish those individuals who have acted out on hate crimes is insufficient. More broadly, we need to have a real national conversation around ‘Who looks American? What does it mean to be American?’”

In an extraordinary display of support, the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship community mounted a successful social media campaign on his behalf, which reached major media outlets and politicians. “The warmth and caring of this group is extraordinary,” he says, “and in challenging moments it simply gets stronger.”

The Long Journey Home

Prabhjot is a new American—and yet that identity feels elusive to him.

His family immigrated twice in two generations, moving from India to Nairobi, where Prabhjot spent much of his childhood, and then to East Lansing, Michigan when he was just 8 years old.

Despite the warm welcome extended by his school’s principal and other well-meaning members of the community, his reception at school was even colder than the Michigan climate: “I was nerdy, shy, and looked different. I was physically and verbally bullied in school. In Nairobi, everyone knew who Sikhs were. Not so in the United States, where Sikhs remain poorly understood.”

That “poor understanding” has increased since the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, but American Sikhs have actually been the target of violence for the past hundred years. As the victim of a brutal attack, Prabhjot knew he was far from unique. He also felt that the attack was a symptom of a country coming to terms, often inelegantly, with a rapidly changing population.

If there’s a silver lining to his ordeal, it has come in the form of a renewed sense of belonging to his Harlem neighborhood and of rising to the challenge of being an American. In the Sikh community, the term sangat refers to a collective way of shaping the future. Prabhjot and his wife Manmeet, with their two-year-old son Hukam, are treasured members of their many sangats—the Sikh community they worship with, the professional community they do service with, and the neighborhood where they live. Through sangat, the outpouring of love and support for Prabhjot and his family has been unceasing.

The man who belongs nowhere yet everywhere continues to live and work in Harlem. His days are over-full. He divides his time between seeing patients, mentoring students, working on the One Million Community Health Workers Campaign, and living the big questions. He’s at home in New York, and in dozens of villages across sub-Saharan Africa. And anywhere else that’s fortunate enough to be touched by this visionary physician-scientist with a heart to match. You could say his sangat is rapidly going global.

At Times, a Persecuted Minority

Asked whether his Sikhism has something to do with his passion for social engagement, Prabhjot explains that service (seva) and remembering the bigger picture (simran) are, indeed, hallmarks of the Sikh faith. Sikhism is a monotheistic, egalitarian religion founded in the early 16th century in the Punjab region of Pakistan and India. Its overarching ethos is to serve humanity (sarbatdhaballa).

But that’s not what his attackers saw on the evening of September 21, 2013.

That very day, members of a Somalia-based Islamist group had mounted an assault-rifle attack on the Westgate Mall in Nairobi. Relieved to learn that his relatives there were okay, Prabhjot went out for a stroll along Central Park North, near his apartment building in Harlem. From behind, a voice shouted, “Osama! Terrorist!” A stream of young men on bicycles proceeded to chase and overtake him. Multiple fists rained down, fracturing his jaw and knocking his teeth loose. He spent the rest of that night in the ER at Mount Sinai, bruised and bloodied.

Prabhjot’s wounds have mostly healed since that gruesome event. His attackers remain at large.

A few days after the attack, appearing on Huff Post Live, Prabhjot expressed empathy and even forgiveness for his tormentors and offered the following comment: “Ultimately, I think to simply go out and punish those individuals who have acted out on hate crimes is insufficient. More broadly, we need to have a real national conversation around ‘Who looks American? What does it mean to be American?’”

In an extraordinary display of support, the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship community mounted a successful social media campaign on his behalf, which reached major media outlets and politicians. “The warmth and caring of this group is extraordinary,” he says, “and in challenging moments it simply gets stronger.”

The Long Journey Home

Prabhjot is a new American—and yet that identity feels elusive to him.

His family immigrated twice in two generations, moving from India to Nairobi, where Prabhjot spent much of his childhood, and then to East Lansing, Michigan when he was just 8 years old.

Despite the warm welcome extended by his school’s principal and other well-meaning members of the community, his reception at school was even colder than the Michigan climate: “I was nerdy, shy, and looked different. I was physically and verbally bullied in school. In Nairobi, everyone knew who Sikhs were. Not so in the United States, where Sikhs remain poorly understood.”

That “poor understanding” has increased since the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, but American Sikhs have actually been the target of violence for the past hundred years. As the victim of a brutal attack, Prabhjot knew he was far from unique. He also felt that the attack was a symptom of a country coming to terms, often inelegantly, with a rapidly changing population.

If there’s a silver lining to his ordeal, it has come in the form of a renewed sense of belonging to his Harlem neighborhood and of rising to the challenge of being an American. In the Sikh community, the term sangat refers to a collective way of shaping the future. Prabhjot and his wife Manmeet, with their two-year-old son Hukam, are treasured members of their many sangats—the Sikh community they worship with, the professional community they do service with, and the neighborhood where they live. Through sangat, the outpouring of love and support for Prabhjot and his family has been unceasing.

The man who belongs nowhere yet everywhere continues to live and work in Harlem. His days are over-full. He divides his time between seeing patients, mentoring students, working on the One Million Community Health Workers Campaign, and living the big questions. He’s at home in New York, and in dozens of villages across sub-Saharan Africa. And anywhere else that’s fortunate enough to be touched by this visionary physician-scientist with a heart to match. You could say his sangat is rapidly going global. ∎

Keep Exploring

-

Read more: The Public Voices Fellowship of PD Soros, in partnership with the Oped Project: Year Four

Read more: The Public Voices Fellowship of PD Soros, in partnership with the Oped Project: Year FourThe Public Voices Fellowship of PD Soros, in partnership with the Oped Project: Year Four

-

Read more: NOT ON MY RESUME: Ming Hsu Chen

- Fellow Highlights

- Fellows in Action

NOT ON MY RESUME: Ming Hsu Chen

-

Read more: Kathy Ku Steps into Leadership as PDSFA Chair

Read more: Kathy Ku Steps into Leadership as PDSFA Chair- Board of Directors

- Fellowship News

Kathy Ku Steps into Leadership as PDSFA Chair

-

Read more: Q&A with MD/PhD Student Silvia Huerta Lopez

Read more: Q&A with MD/PhD Student Silvia Huerta LopezQ&A with MD/PhD Student Silvia Huerta Lopez