- Fellow Highlights

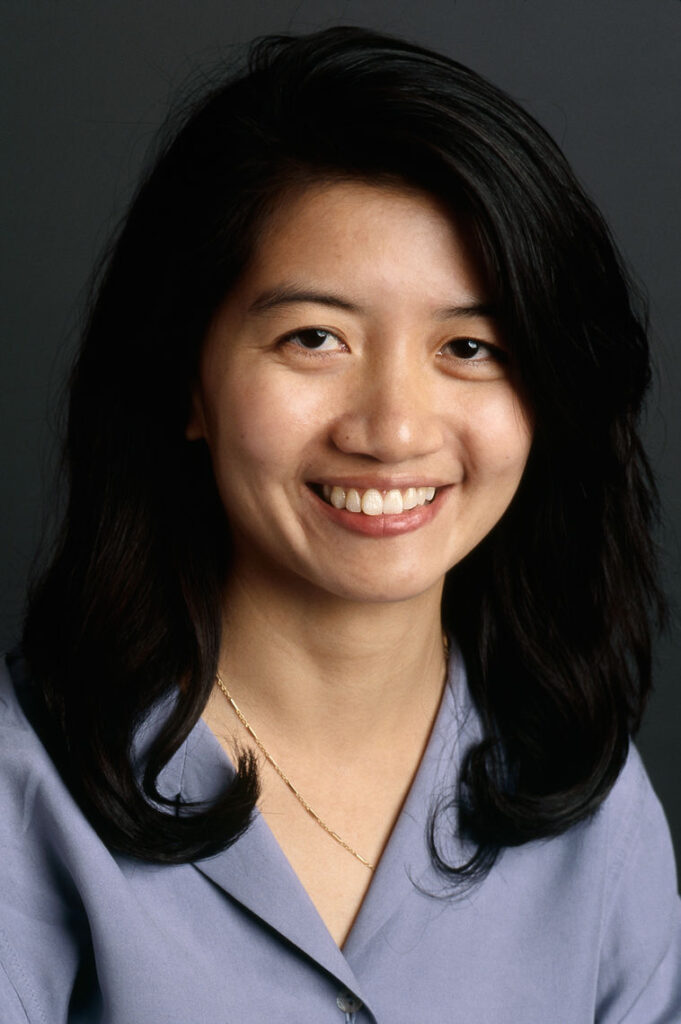

Q&A: How Thuy Thi Nguyen’s (1999 Fellow) Parents Raised the First Vietnamese American College President in the United States

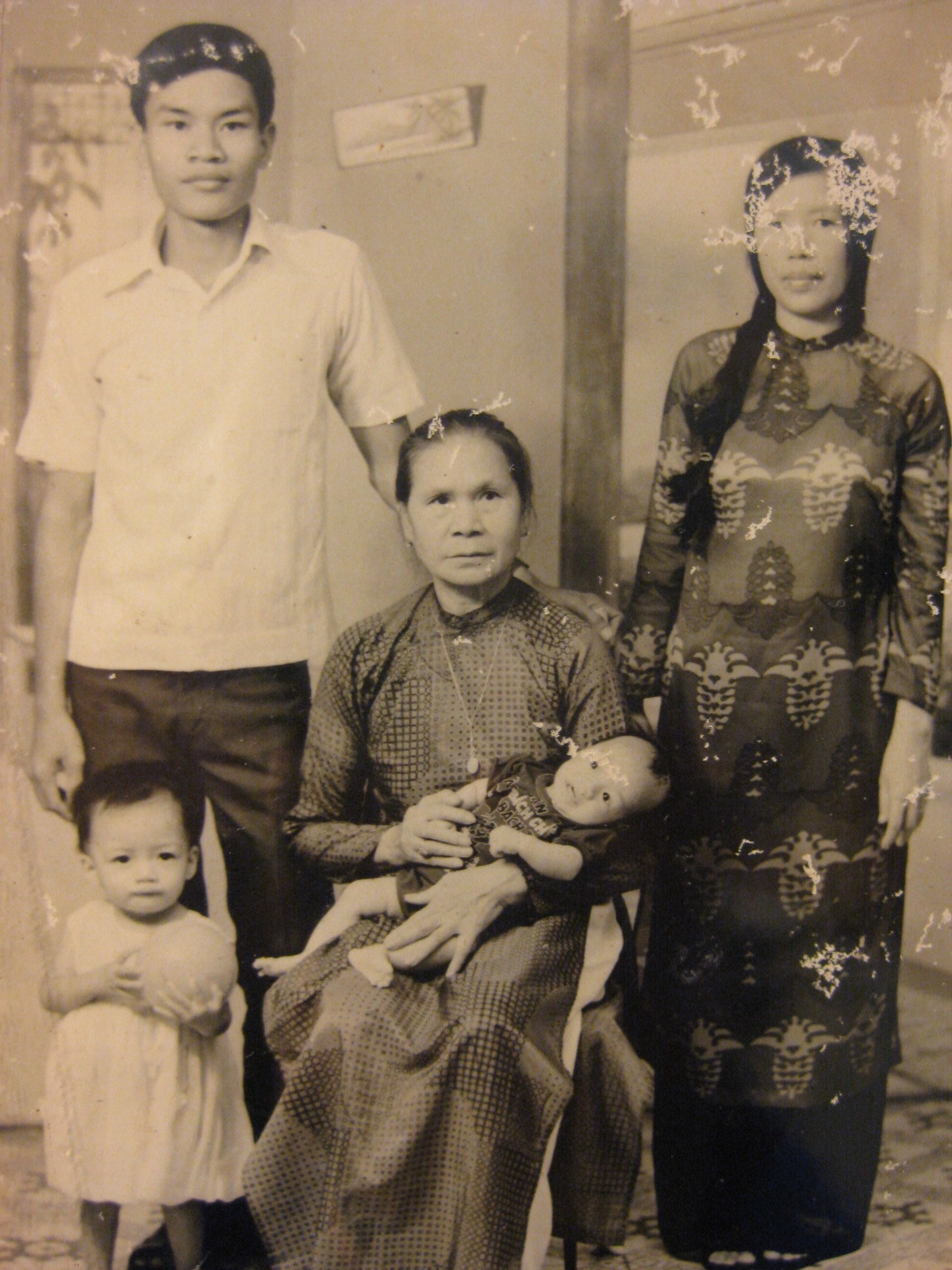

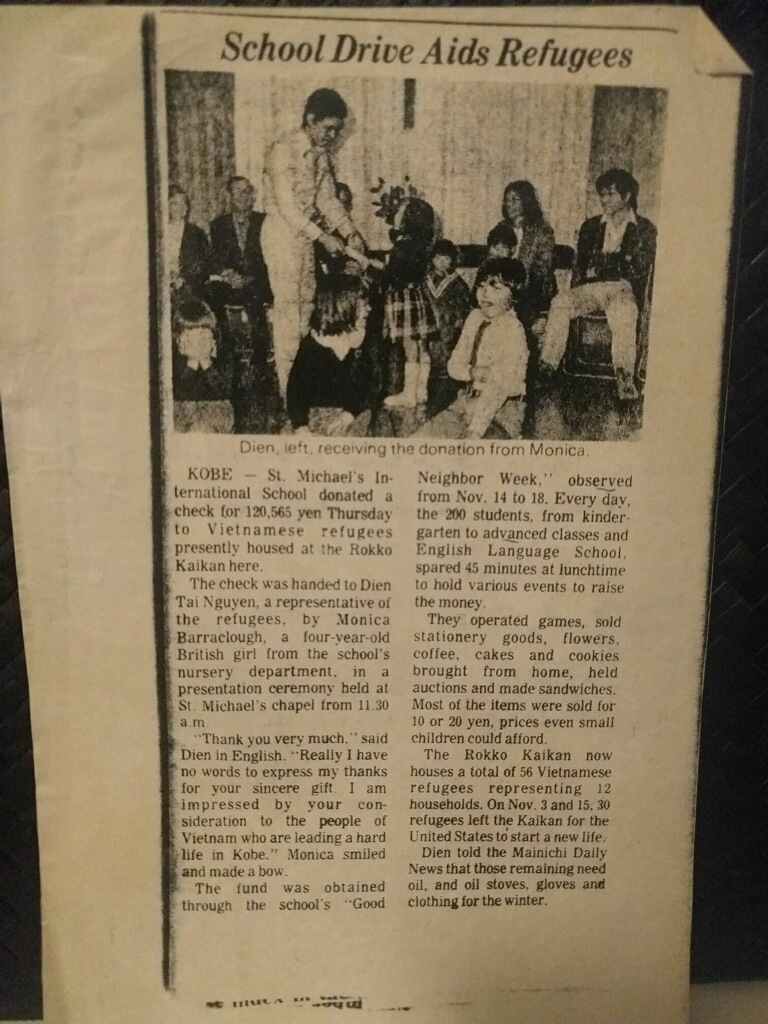

As Thuy Thi Nguyen’s elementary school teachers in New Orleans sent home increasingly complex homework, her eager parents were able to help her less and less. Thuy’s parents had risked everything when they fled Vietnam by boat after the fall of Saigon with their two toddlers, Thuy and her younger brother. They drifted in the Pacific Ocean for more than twenty days before finally being rescued by a commercial ship. They were taken to a Japanese refugee camp and eventually came to the United States.

When it came to their daughter’s education, Thuy’s parents were on it. They may have lacked the English that was needed to help their eldest with schoolwork, but they did everything in their power to make sure that she had exactly what she needed to succeed—from ideal lighting for her homework to a precisely scheduled commute.

The thing that stands out most to Thuy about her parents’ focus on education is the enormous classroom-size blackboard that her father found and brought home to their small apartment. “They weren’t able to teach us, but they were able to provide us with the environment that we needed to be successful,” she explained.

“My parents had this philosophy—and it’s both an immigrant and Vietnamese thing—Đâu xuôi, đuôi lot, which means ‘If the head could get through, so could the tail.’ They focused a lot on me because the belief was that I would pave the way for my younger siblings.”

When they heard from their family members who lived in California that the Golden State had better educational opportunities, Thuy’s parents moved the family to Oakland, where Thuy started high school.

Now, nearly twenty-five years later, Thuy is the incoming president of Foothill College. She will be the first Vietnamese American president of a community college in California, and possibly in the country.

This interview was conducted and condensed by Nikka Landau. An updated and condensed version appears in the 2016-2017 edition of The New American.

Can you tell me about yourself as a child?

I was pretty obedient. I had a little sassiness in me, but generally speaking I did not get in trouble. I was a little bit of a nerd. I loved school. I loved reading. You were more likely to find me in the library reading than at recess. I’m the oldest of eight children so I also had to really help and guide my siblings.

Is that how you developed your love of teaching—as the oldest child?

I love teaching. I don’t know where it started, but if I can go back to my earliest memory of teaching, it was in eighth grade. My father kept on being laid off from his job in New Orleans so we moved to Lake Charles, but after a year we moved back to be close to our family. As a consequence, I didn’t take the requisite exams to be in a more advanced math course. Nevertheless, my eighth-grade teacher felt that I had the skill set to take the more advanced class with another teacher so she tried to get me in, unsuccessfully, and then later, she had me teach her math class! Ms. Albert . . . God bless her.

After arriving in the United States, your family moved between Wichita, New Orleans, and Oakland. Which place sticks out most in your memory?

What’s interesting is that at one point we lived on a street called Saigon Drive in New Orleans. They literally called the community we lived in Village de L’Est, which means “Village of the East” or “New Orleans East.” The majority of the people in the village were Vietnamese refugees. The community gathered itself and built the first Vietnamese-owned church in America, the first Vietnamese-owned Vietnamese language and bible school—and we lived within that community. Streets were named in Vietnamese. As you can imagine, that’s an interesting environment to grow up in. You are in America but very much in a Vietnamese community. We weren’t watching a lot of Saturday morning cartoons; instead we were watching Chinese kung fu movies dubbed in Vietnamese. We were really living an immigrant life in this larger community.

What kind of work did your parents do?

In the United States, my mom has always been a homemaker. My dad is retired now. He worked as a machinist, construction worker, landscaper, and a security guard at different points.

What did your parents do when they lived in Vietnam?

My mother married a little bit later than was the norm then—at about age twenty-four, which was a little bit unusual in Vietnam back then. She was a secretary for the American military. She is still very proud of that because only a few women were selected to work with the American military. My father worked in the Navy. He had natural leadership qualities. He knew a little bit of English and would help with limited translation.

What lessons did your parents teach you about leadership and success?

My parents didn’t necessarily say to me, “If you want to lead a group of people, this is what you do; read this book.” They didn’t have that kind of formal knowledge. But what they did have and what they did teach me about are the characteristics that make one a good person and the desire to be successful at whatever you do.

When we lived in a big low-income apartment complex, my mother would go to each of the units and share the food she had made with our neighbors. She would always be an ear for our neighbors whenever they had problems. And you know, you inevitably model after that when you see a person who is that giving, who isn’t just about me, me, me.

My father is such a great thinker. He thinks about policy and politics. He has a very intellectual and curious mind. At dinnertime we always had fascinating conversations about various issues that were happening in the country, in our neighborhood, or even in our daily lives. We would talk about lessons learned from those events; and stories about Vietnam. My parents fled Vietnam because they had a real fundamental belief around freedom—both religious freedom and political freedom. They strongly believe in a free society and in human rights. They are very principled. Those were the kinds of things that we talked about. Those discussions really shaped me.

Who have your mentors been?

I have so many mentors and guardians. I call them my guardians because they don’t just tell me and coach me on what to do—they make efforts to open doors for me. My all-time mentor is my mother, though. Her unwavering confidence in me in turn has sustained my own self-confidence.

I also have a guardian and coach, Elihu Harris. He was the mayor of Oakland, and then he became the chancellor of the Peralta Community College District. He audaciously called me when I was twenty-eight years old and asked if I wanted to come over and be the interim general counsel of Peralta. I was barely out of law school! A year after I started, I became the permanent general counsel. I was at Peralta for over eleven years. He just opened that door and has guided me throughout the years. After a certain point, he said, “Thuy, you’ve seen a lot and you’ve contributed enormously for Peralta as a lawyer, but it’s time for you to go out there and let the world know who you are too.” That really pushed me. He was the one who first suggested that I be a college president. At that time I said, “That’s okay—I’ll remain a lawyer.” But clearly he planted that seed, and it grew.

What will your first priority as the Foothill College president be?

My highest priority will be student equity and making sure that all of our students are successful, not just a few. Whatever challenges that they come with, I want to ensure that we will be able to help them succeed. There’s a tremendous amount of social justice in that—just making sure that success is for all.

What advice do you have for immigrants and refugees who are picking a college or university?

Community college is such an incredible opportunity for immigrants and refugees, especially if they came to the United States later in life. Community college is a place of first chances, second chances and last chances. That’s why I say, “There’s nothing more American than community college.” It’s open to everyone regardless of socioeconomic background.

You received the Paul & Daisy Soros Fellowship when you were in law school at UCLA. What is your impression of the mission of the Fellowships now?

I am thankful that Paul and Daisy Soros, in their wisdom, appreciated the importance of immigrants and understood that education is key to unlocking the full potential of immigrants. I think it is brilliant of Paul and Daisy Soros to have decided to invest in education. The success of the Fellows is so critical to the conversation around our country with regard to recognizing the contributions that immigrants make.

The two central components of the Fellowship program—immigrants and education—I think literally describe who I am and what I do, respectively. I am an immigrant who works in education. I really applaud Paul and Daisy Soros for their vision and I hope to prove worthy of the honor of being a Paul & Daisy Soros Fellow. The Fellowship not only assisted me financially, it also gave me the added confidence I needed at the time. I was in law school, and I felt my selection for the Fellowship validated my aspirations and affirmed that I was essentially on the right track. ∎

Keep Exploring

-

Read more: NOT ON MY RESUME: Jamaji C. Nwanaji-Enwerem

Read more: NOT ON MY RESUME: Jamaji C. Nwanaji-Enwerem- Fellow Highlights

- Fellows in Action

NOT ON MY RESUME: Jamaji C. Nwanaji-Enwerem

-

Read more: New Play by 1999 Fellow and Former Ambassador Julissa Reynoso Opens at The Public Theater

Read more: New Play by 1999 Fellow and Former Ambassador Julissa Reynoso Opens at The Public Theater- Fellow Highlights

New Play by 1999 Fellow and Former Ambassador Julissa Reynoso Opens at The Public Theater

-

Read more: The Public Voices Fellowship of PD Soros, in partnership with the Oped Project: Year Four

Read more: The Public Voices Fellowship of PD Soros, in partnership with the Oped Project: Year FourThe Public Voices Fellowship of PD Soros, in partnership with the Oped Project: Year Four

-

Read more: NOT ON MY RESUME: Ming Hsu Chen

Read more: NOT ON MY RESUME: Ming Hsu Chen- Fellow Highlights

- Fellows in Action

NOT ON MY RESUME: Ming Hsu Chen